Kate Lowe | January 2021 | London

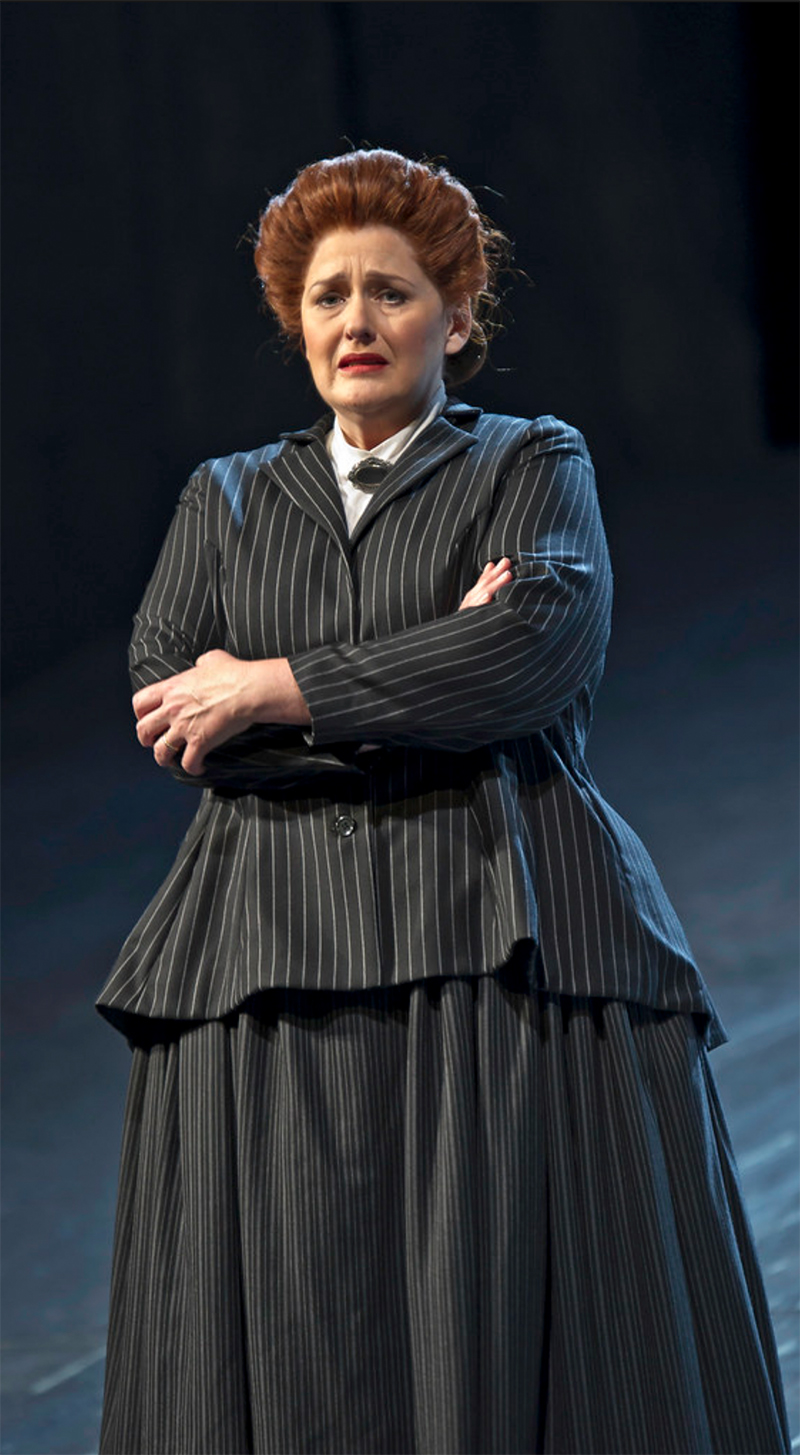

Catherine Wyn-Rogers’s 40-year career has taken her all over the world since leaving the Royal College of Music in London. She began principally as a concert singer, working with many important ensembles both in the UK and internationally, and then began to sing much more regularly in opera, appearing at the Royal Opera, Glyndebourne, the Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich, La Scala in Milan, the Metropolitan Opera in New York, Chicago Lyric Opera and the Tokyo National Opera, working with Zubin Mehta, Bernard Haitink, Sir Andrew Davis, Robin Ticciati, Trevor Pinnock and Harry Christophers, amongst many others. Her repertoire is wide-ranging, from baroque works with period ensembles to contemporary music; her opera performances range from Monteverdi through Wagner to Britten and Tippett. Her many recordings include Britten’s Peter Grimes with Edward Gardner and the Bergen Philharmonic, The Dream of Gerontius with Daniel Barenboim, and Handel’s Messiah with Harry Christophers and The Sixteen. She is a member of the vocal faculty at the Royal Academy of Music.

What is your earliest musical memory?

It was probably my school choir. I do remember singing ‘All things bright and beautiful’ down the octave when I was at junior school, but I think it was really my school choir at the local grammar school in Chesterfield, England. When I joined in my early teens, there was a little solo which every student had to sing individually in a rehearsal, but which I was eventually asked to perform. I remember when it was my turn to sing, and the choir mistress exclaimed ‘Now, there’s a voice!’ – which took me aback. From that moment onwards, I was bitten by the singing bug! Prior to joining the school choir, I started learning the piano at around the age of seven, which meant that I had to learn how to sight-read. I then went on to fail my grade one exam (which I understand is quite an achievement), and stopped completely during secondary school. However, I picked it up again later on by playing unison hymns, and eventually took my grade six exam in order to get into conservatoire (Royal College of Music).

And your first experience of a live stage performance/opera?

My earliest memory of seeing an opera was in Sheffield – and it had a big impact on me. My mother (who was an enthusiastic concert attendee as well as choir member) took me to see Verdi’s La Traviata, performed by Sheffield Grand Opera, and I loved it. I am still very fond of this opera – it has some fabulous melodies. It wasn’t a lavish production, but the opera society nevertheless made it work, and it has stayed with me ever since.

When did you know that you wanted to pursue a career in singing and opera?

It was my experience of singing in choirs (school choir, then the local philharmonic choir, as well as the church choir) that really got me started, and oratorio and opera came later. My mother and both my grandparents sang in choirs, and my grandmother was an organist back in Wales, so I was surrounded by the choral tradition. I remember how they became involved in the Gregynog Music Festival in Wales – a musical festival run by the Davies sisters where people like Kathleen Ferrier, Isobel Baillie and other renowned singers would come to perform. Little did I know then that I would be asked to perform there as a soloist in the St John Passion many years later! Whenever a choir was needed, my grandparents would be roped in! It wasn’t such a global world at the time, so the stars of the day would go and perform in these small venues – something that now seems quite incredible.

In addition, the Davies sisters were great patrons of the arts, supporting music, painting etc. We needed this support then, and need it even more at this current time… So my singing started off through choirs, and was further encouraged by a wonderful teacher and oratorio singer by the name of Pamela Cook. I recall her saying to me, ‘I don’t know what your voice is going to do, but you’re going to be a singer. We’ve got a lot of work to do, but we will get you into conservatoire.’ She didn’t say ‘you might have a chance at being a singer’ but that it was a certainty. She further added that I would need theory and piano skills, and that I would be taking part in festivals to gain performance experience. Here was someone who really knew what they were talking about regarding singing, giving me the encouragement and guidance to pursue it as a career.

Who was your biggest inspiration when you were starting your career?

It has got to be Dame Janet Baker. She was in full flight both before and during my studies at RCM (Royal College of Music), and I had watched her perform in Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius on TV and also in a recital in Nottingham before I came to college. I was entranced by what she did with repertoire, and by her commitment to text, and looked up to her as the definitive mezzo. I was also heavily inspired and encouraged by my teacher at RCM, Meriel St Clair, whom I was desperately hoping I would be given as my principal teacher before I arrived at college. My dream became reality as I was lucky enough to be assigned to her by Sir David Willcocks (director of RCM at that time), after my audition at RCM. Although Meriel never took on a singer she hadn’t heard in person, after David had heard me sing in my audition he gave me a scholarship and asked Meriel to teach me – and for me it was the perfect match. I needed her painstaking care, as I was a bit stolid and was wrapped up in making sound rather than interpretation. I knew I had a voice, but I didn’t know what to do with it until I was taught by Meriel.

You have spoken of your enjoyment of singing in the native language of your audience. How does this impact on the singer and on the audience?

There is something very special about singing in the language of the audience to whom you are performing. When I first sang in choral societies, including the Bach Choir under the direction of Sir David Willcocks, we sang many oratorios in English, which meant that I learnt them all cover to cover and also understood them all deeply. We sang in English rather than German or Latin because we were singing to an English audience – just as Bach composed in his own native language (German) so that the congregation would understand everything. The impact of the piece is completely different to singing in a language that is not your mother tongue; there is a directness and immediacy to the piece. Rather than just getting the odd word now and then, there is an immediate understanding, which makes the text seem incredibly real. Oratorios have since come to make up a substantial part of my career, having performed as a soloist in numerous performances for a span of ten years.

Your voice has taken you all over the world, including Hong Kong and Beijing. What were the highlights of these trips to Asia?

I have some wonderful memories of performances in Asia – specifically in Hong Kong, Beijing and Tokyo. A highlight was performing as the alto soloist in the B Minor Mass with the Bach Choir at the opening ceremony of the Hong Kong Cultural Centre on the harbour in 1989. It was in the presence of Prince Charles and Lady Diana, and felt incredibly special. In fact, I performed there several times with the Bach Choir, including in Handel’s Messiah when I performed the alto solos, and I remember it being a magnificent space. These concerts were such fun, and I made many friends in the process. Another highlight was a performance of Britten’s Peter Grimes with Tokyo Opera, which we had performed beforehand at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. There were just four English performers (including myself) in a cast made up of Japanese performers, as well as a Japanese conductor, which made for an incredibly special international experience. Japan is such a beautiful place. Finally, I have very fond memories of singing Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen with Andrew Davis (a great friend of mine) and the BBC Symphony Orchestra in Beijing in 2019. The audience was so appreciative, which makes it all the more enjoyable for the singer!

Britten’s opera Peter Grimes and Elgar’s grand oratorio The Dream of Gerontius are works in which you have performed many times, and that are close to your heart. What do you feel makes each work so timeless?

Both The Dream of Gerontius and Peter Grimes contain universal themes: Gerontius focuses on the spiritual, Grimes on humanity, so there are aspects in both to which everyone can relate. Gerontius (a word meaning ‘old man’ in Ancient Greek) uses the text from a heartfelt poem of the same name by Cardinal Newman (an influential member of the Roman Catholic Church in Britain during the nineteenth century), and tells the story of a man, Gerontius, who is dying in his faith, surrounded by friends and with a priest in attendance. As these friends (the chorus) sing prayers for the dead, he is sent on his way to meet God (‘Go forth upon thy journey, Christian soul’), accompanied by a guardian angel (the mezzo lead role), who, unbeknownst to Gerontius, has been with him throughout his life. However, the angel warns him that he will be sorry he asked to see God, as when God appears to Gerontius he will be filled with joy, but it will also hurt – such is the purifying fire of God. In fact, one of the loudest chords in any orchestral work at the time was at this point: when Gerontius meets his maker. This work is full of Catholic dogma, but the inspiration of it and the way in which Elgar has set the poem to music is about the universality of everyone’s journey. We will all die at some point, and do not know where we will go, and, even if the process described in Gerontius is not true, the thought that those who have gone are being looked after by a caring creature such as the angel is extremely comforting. You might ask why it is entitled a ‘Dream’. It may well be, but, for a singer, it feels much more like a narration of what happens when we die rather than a mere dream. It is also worth noting that Catholics did not have the vote at the time Elgar wrote the work, which made them feel very much like outsiders. This might therefore provide a solid reasoning behind the passion conveyed by Elgar in the piece: he wanted to share fervently his religious beliefs with the public.

Britten’s masterpiece Peter Grimes deals with quite different topics, but is equally powerful. Taken from a set of poems entitled The Borough by George Crabbe (1810), and set in Britten’s hometown of Aldeburgh, it tells the story of the fisherman Peter Grimes – an outsider who is determined to catch more fish than anyone else in the town, and who ends up responsible (through accidental circumstances) for the deaths of two young boys whom he recruits as helpmates on his boat. At the same time, Grimes is cared for by the town schoolteacher, but does not reciprocate her love, and he is eventually ostracised by the local townspeople. Although it is apparent that Grimes is physically violent and is not the most likeable character, he nevertheless experiences some very human emotions, and the story addresses other themes such as victimisation and mob rule. We see Grimes turn mad at the end of the piece, as his conscience cannot cope with the death of two children. He is afraid it might happen again, and so takes a boat out into the sea and is not seen again.

What has been your most memorable performance to date and why?

There have been multiple memorable performances over the years for which I feel very lucky. Of course, debuts at La Scala, the MET and Covent Garden stand out, but there are others too. Performing ‘Rule, Britannia!’ at the Last Night of the Proms in 1995 was an incredibly special event for me, and I felt very privileged to be a part of it. Another memorable occasion was the royal wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana in 1981, when I was part of the final chorus of ‘Samson’ (Let their celestial concerts all unite) in the Bach Choir supporting Kiri Te Kanawa. It was a simply wonderful day. The singers had to arrive very early, and we were all bussed in from different parts of London in order to rehearse and then perform at the wedding. I remember the hordes of people lining the streets outside St Paul’s Cathedral in London (the wedding venue), cheering at anything that moved. When the couple said their vows in the ceremony, the congregation in the cathedral remained quiet and po-faced – but outside the crowds cheered. It was a beautiful moment. In the evening, I had to get down to Glyndebourne as I was performing in the chorus of Fidelio that evening, and after the performance there were fireworks for royal wedding day. I remember the positive spirit of everybody at the time. Little did we know how things would change – but, at that moment, everything felt joyous. Another highlight would have to be the production of Peter Grimes which we performed on the beach at Aldeburgh for the Britten centenary in 2013. I think Britten would have said he wouldn’t have wanted it performed in this manner because it might have been compromised by all the technical difficulties, but I hope he would have realised that it was done with incredible care, and was not at all gimmicky. An enormous amount of technical expertise went into the production. All the singers sang to a pre-recorded orchestra on tape (the orchestral members of the Britten–Pears School, no less), and each member was miked and had earphones in order to listen to the orchestral accompaniment – all played back by a man in a tiny hut dug into the shingle, which is where the conductor was! It was quite an amazing achievement, and the sound of the North Sea in the background added so much to the production. The set consisted of a broken-down jetty, with boats positioned here and there, and I can remember the final chorus of the production where the mob chorus sing ‘Peter Grimes!’, with regular intervals in between. In these intervals, the waves crashed on the shore – it seemed to be perfectly timed! Although Britten specifically stated that the sea must not be a character in his opera, in our production the sea was a backdrop, and the performers sang out facing the audience. This seemed fitting as the show is about people, and must not draw too much focus onto the sea.

How do you go about learning a completely new role?

You should always learn the text first, especially if it is in a foreign language. It is important to unpick problems you might find in the pronunciation, and then to develop a feeling of fluency. You must also get an idea of the whole story if you are talking about an operatic role, and know the background. I also ask myself the following questions: why am I singing what I am singing, and when am I singing it in terms of the plot? Furthermore, what is my relationship to the characters around me? It is essential to know not just your own part but what is around it. Only then should you start looking at and learning the music. When you do so, be careful to always start by getting the music right the first time round. I say this because your brain will try to fit what you are learning into a pattern it already knows, so it is very easy to memorise wrong intervals and intonation. Through my teaching experience, I have also noticed that students tend not to be as careful with rhythm as they are with pitch – but rhythm is just as important! The pitch has got to fit the accompaniment, and words have a spring in them. Having a strong rhythm framework is vital. Finally, the score with the musical notation is not the music but only the guidelines for how the music should sound! Musical accuracy is absolutely important, but you’ve got to punch your way through the paper score and reach the music on the other side. Make sure that you’re actually saying the words and meaning them, and not just making the sound of words. What is the composer ultimately trying to say?

As a teacher at RAM, what are your key tips for improving vocal stamina?

I believe that vocal stamina comes from a combination of muscular development, experience and practice. Half of the job of singing is speaking, and you cannot change your larynx, but you can develop your breathing over time. When being used well, it is incredible how much stamina the vocal chords have. But it is important to pay attention to how your voice feels. When you have been singing for a long length of time, stop and gauge how your throat is afterwards. If after lots of rehearsal your throat is sore, you are maybe not supporting the voice properly. You will probably need to stop and get some technical help with either a singing teacher or a voice specialist. The mind goes straight to the larynx when it is worried about the throat, so, if your throat is not feeling well, it is important to sing more normally than ever. Breathe as if nothing is wrong, and if at the end of that the throat or vocal chords are still hurting or not feeling right, then it is best to stop and rest – if rest for a couple of days doesn’t help, then seek expert help. Never adjust technically to make your singing ‘feel better’; try hard to sing as normally as possible so that your breath and support work well and the throat isn’t strained in any way.

In today’s world, there are many talented classical singers, fresh out of conservatoire, and all fighting over a small number of roles and young artist programmes. What would be your advice to them regarding establishing yourself in this competitive arena?

This is a very difficult time everywhere for singers just starting out in the profession, as COVID-19 has only exacerbated the already competitive nature of the singing profession. My best advice would be to try to make your own opportunities, be that through online auditions, concerts or other methods. These are difficult circumstances, but there are still ways to make music. In terms of auditions, I would recommend going into an audition with the mindset that it is performance practice and not the be-all and end-all, even if it might feel that way. I like a quote from the actor George Clooney, who said the following about auditions: remember, if you are turned down, you’re no further back than when you entered the audition room. There is a lot of truth to this. There are many criteria that panels are looking for, and their decision is not necessarily all about your vocal quality but about how you fit in with the colleagues you might be singing with. Their decision could all come down to your height, for example! Remembering this as you go into an audition is important both mentally and physically so that you simply enjoy the experience of singing for the panel and do your best. A physical exercise I would recommend doing before entering the audition room is to take three deep breaths. This will take the edge off your nerves, and will allow you to breathe better in the audition itself. Accept that you will be nervous, so prepare for this. Furthermore, if you really perform the meaning of the words and music, you won’t really have time to worry about how nervous you might be. Your mind should be on what you bring to the music you’ve chosen. Overall, my main advice for entering the singing profession would be to present yourself as the best you can be, and also as the best colleague you can be.

What genres of music do you enjoy listening to in your spare time, and what do you think a classical musician can learn from other genres?

It may seem odd, but I don’t often find myself listening to singing in my free time, as it is not a completely relaxing experience! I’m constantly judging and listening very carefully to the voices, and so much prefer listening to orchestral music to relax. However, I’ve always been a big fan of the Beatles, and have recently discovered Buena Vista Social Club – I love their cool and soothing tones! Another favourite is Caro Emerald, whose 50s swing arrangements are great fun and so catchy. She’s also a brilliant singer. And, of course, Ella Fitzgerald. How could I forget her? I think the freedom which these artists display with their voices and words can teach us more formal and classically trained singers a great deal.

What three qualities do you think make a successful singer?

There are many aspects, but I would say, in order, these three things: curiosity, receptiveness and imagination. Of course, you need a good innate voice, but there are many more things that make a singer. It is important to always be curious about any piece of music you sing, and also to be receptive to constructive criticism. And then imagination is vital: you need to be able to own the piece of music you are singing, and to be able to bring it alive.

How has the COVID-19 situation affected you and what is your advice for singers regarding how to make the best out of the time while we are all at home?

I am very fortunate to have been able to continue teaching my students at the Royal Academy of Music online throughout the pandemic, and am very impressed with how the singers have thrown themselves into the process. Although it is an awful situation, they have worked very well online, and many have made incredible strides forward. This is the time to focus on our own vocal technique in order to come back onto the stage with renewed strength. We have to all keep strong and optimistic during this time, because all the opportunities for musicians will eventually return. During the pandemic, I have often found myself thinking about those who lived through the horrors of the Second World War. There was an atmosphere of fear, anger and rage for six years – and yet, when it was all over, people picked themselves up and carried on. We can do the same – in some ways, getting to know new repertoire and working intensively on technique, while waiting for things to get back to normal, can be very fruitful.

And finally, what are your upcoming musical projects this year?

At time of writing (and COVID permitting), I am very much looking forward to several projects this coming year, including performing in Madrid in a production of Peter Grimes, directed by Deborah Warner, that will transfer to the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden.