By Tamami Honma | Nov 2017

In our age of increasingly compartmentalized areas of expertise, it’s easy to get lulled into the idea that dedicated, rigorous study within a field will be sufficient to realize your maximum potential. It is the case, however, that collaborations and ideas often cross disciplines. So much so that for example in Finland, one of the world leaders in public education, there’s a trend towards project-based learning and doing less with strictly separate subjects of study.

This article in three parts will focus on the world of art and its relationship to the world of music because I believe musicians can benefit enormously by expanding the scope of their interpretations and understanding of contemporaneous performance practice to embrace the visual arts. The more we know about the cultural context in which composers worked, the more tools we have as performers to interpret what is on the written page long after the composers and any of their contemporaries, who could have given us more clues, have already passed.

Whether aiming for historical accuracy or searching for inspiration, among the clues we can examine to feel closer to the composer’s intentions are his/her own sketches, contemporaneous writings, and their state of mind and affairs at the time of writing. Already by the late 1800s Ferruccio Busoni was criticizing traditional music notation and advocating that the notation of music was already a transcription of the music in the composer’s mind, and that it was the performer’s job to complete the compositional process. For much of the period in which ‘classical music’ was being written there were no movies, TV, internet or even photographs. However, there was art – drawings, prints, paintings, and sculpture – which must have all had an enormous impact on how people perceived the world.

One important way in which we can identify cultural trends that may have acted as cross winds between the arts and music is to consider the labels we attach to different period styles. The terms classicism and romanticism, for example, are both applicable to the arts and music so it seems reasonable to consider whether the shared attributes between these movements can deepen our understanding of their meanings. But we have to be a little careful: when we classify groups of artists, philosophers, authors, composers and architects, there is a danger of watering down individual traits for the sake of imposing tidy categories.

As a musician, I believe it is crucial to at least have some awareness and understanding of the dialogue that has shaped artistic and musical movements. In both arenas, borders and rules are still today constantly challenged, examined, and then further explored to make progress beyond the status quo. Through these efforts we can reach a better reading of the score and bring better informed interpretations to performances.

NATIONALISM

IN ENGLAND

By including traditional folk tunes from a particular country, or by basing works on local historical figures or myths and folklore, art and music can both wave national flags high. Since the advent of music long, long ago – voices and songs were critical to help convey the individual identity, to mark social celebrations and to actualize ritualistic events, and to narrate and pass along news and stories. It is no wonder that politics seeps into every biography of our known composers and compositions in some form. In 16th century England there was an explosion of art to glorify the reign of Elizabeth I (largely due to her patronage), preceding the Age of Enlightenment. Art, poetry and music were dedicated to her and members of her court in abundance and there were many portraiture commissions during this time. A prominent example is the Armada Portrait, an allegorical painting that depicts her in resplendent dress, surrounded by symbols of her power against a backdrop representing the defeat of the Spanish Armada, a momentous historical event that was her country’s greatest military victory. During her reign, William Shakespeare immortalized earlier events of British history in his plays, while William Byrd composed prolifically for the virginal, an early version of the harpsichord that was Queen Elizabeth’s favorite instrument to play. Such developments among many others laid the foundations for a new British sensibility in the arts, literature, and music.

A century later Purcell furthered the sense of British identity in music with his settings of Shakespeare’s plays and commemorative works for Queen Mary. In the 18th century JMW Turner and John Constable were capturing visions of quintessential English landscapes including stormy seas, fog over the River Thames in London, and country scenes. In the 20th century, Ralph Vaughan Williams, one of Britain’s most important modern composers, wrote that ‘The art of music above all the other arts is the expression of the soul of a nation.’ Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis not only quotes a much earlier English composer but conveys an unmistakable pastoral quality that evokes the rolling hills of the English countryside. Other examples of salutes to Britain are Edward Elgar’s ‘Enigma Variations’ and Benjamin Britten’s ‘Young Musician’s Guide to the Orchestra’ which quotes a theme by Henry Purcell.

IN RUSSIA

Just as Queen Elizabeth’s patronage is credited with fueling the golden era of new works of art and music in England, Catherine the Great in 18th century Russia also glorified her crown and court and ensured her legacy lived on in art and music. Robust state support continued long after her passing and was largely responsible for the wealth of art and musical works that continued to come out of Russia in the 19th century and beyond. Some nationalistic fervor was also home-grown. The group of amateur Russian composers known as ‘the Five’ that consisted of Mily Balakirev (mathematician), Alexander Borodin (chemist), César Cui (military officer), Modest Mussorgsky (member of the Imperial Guard and later in the State Forestry Department), and Nikolai Rimsky- Korsakov (naval officer) all worked to create a distinctly Russian sound in classical music. It may have been their jobs in the military which added even more fuel to their nationalist spirit. Indeed, Rimsky- Korsakov wrote his first symphony while circumnavigating the globe.

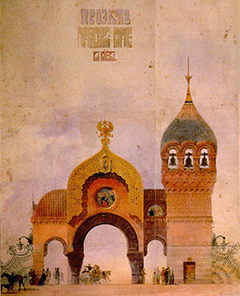

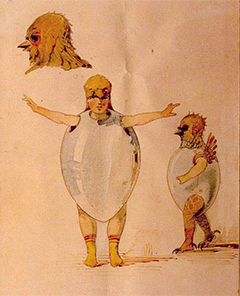

Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition also represents one of the best known and most direct influences of art on the world of music. Mussorgsky was inspired by his visit to an art exhibition of paintings by Viktor Hartmann and his work aurally evokes the images as though walking past them by also including ‘promenades’. The images were scenes from Russian folklore making them ideal examples of the the Five’s nationalistic movement. Pyotr Tchaikovsky was not so closely affiliated with the Five’s ideas but Russia wins the battle every time in his enduring 1812 Overture.

In the world of art, Viktor Vasnetsov, Fyodor Vasilyev, Ivan Bilibin and Alexey Savrasov are considered some of the best representatives of the Russian romantic nationalist movement. Artist Isaac Levitan searched for the ‘soul of Russian nature’ and another, Ivan Shishkin famously said, ‘My motto? To be Russian. Long live Russia!’

IN SPAIN

No discussion of Nationalism in music could forgo mention of Spain, a land where impassioned flamenco dancers flash brilliant red costumes, bullfighters proudly fire up the crowds in controversial contests between man and beast, and people regularly celebrate fiestas late into the night. With fiery colors, intense romanticism, and implied strumming of guitars, images of Spanish landscapes abound in Isaac Albéniz Iberia and in works by Joaquín Rodrigo. References to the national dances Bolero, Fandango, Flamenco, Jota, Sevillanas, and Zarzuela add an unmistakable Spanish signature to numerous artistic and musical works. The influence of these nationalistic traits has sometimes been deliberately fostered. Joaquin Turina studied in Madrid and then in Paris where he fell under the spell of Debussy and Ravel, only to be told by Albéniz, that he should eschew French influences and return to his Spanish roots. Enrique Granados needed no such encouragement in writing Goyescas, a magnificent piano work considered his crowning achievement that was directly influenced by the paintings of Francisco De Goya.

IN THE UNITED STATES

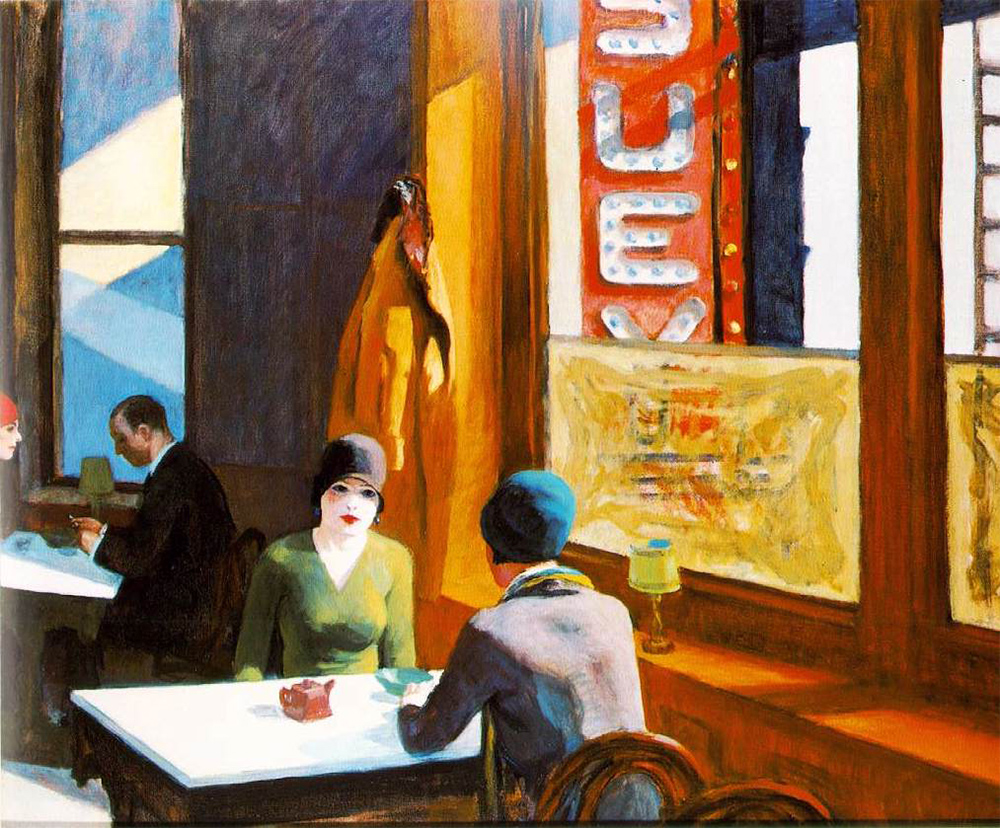

In the early 20th century the United States was still a young country compared with Europe looking for its own cultural identity, and it’s perhaps not surprising that artists and composers there sought to define something prototypically American. Aaron Copland integrated Shaker hymn melodies into Appalachian Spring and included American western themes in Rodeo; Norman Rockwell captured the American home theme in his writings, paintings and illustrations, Edward Hopper painted modern everyday American rural and urban scenes. George Gershwin brought African American influences such as jazz into the classical arena, including the actual characters in his opera Porgy and Bess. The development of the ‘Hudson River’ and ‘Rocky Mountain’ schools were a result of artists’ attempt to depict landscapes of the great American wilderness. A new country needed its own story and art and music were the most powerful vehicles for creating this new vision.

IN OTHER COUNTRIES

Of course, these are a just few examples of nationalism in music and art. There are numerous other examples including such works as the Peer Gynt Suite by Edvard Grieg in Norway, Finlandia by Jean Sibelius, the Polonaises of Frédéric Chopin, Toru Takemitsu collaborating with Akira Kurosawa on Japanese films, George Enescu Two Romanian Rhapsodies, Johann Strauss’ waltzes that remind us of the gala balls in Vienna and the winding Danube River. Also many of Béla Bartók’s works feature Hungarian folk tunes that he made a mission to collect by capturing on recordings in remote villages, and in China the Yellow River Piano Concerto, which appeared during the Cultural Revolution, was intended to be a statement about the Chinese national character.

Parts II of this series will be published in the next issue of Vantage. Tamami will further explore the interaction of art and music in Impressionism, Baroque and the Age of Reason, Classicism, Romanticism, Modernism, Dadaism and the Avant-garde movements.