Vantage Music & Alex Ho | October 2020 | Hong Kong

The 2005 music rhythm game Guitar Hero took the world by storm, but back in the eighties Hong Kong had already produced her own guitar hero, the jazz guitarist Eugene Pao. In this interview, Eugene looks back on his path to success, and shares with us the interesting stories surrounding his spectacular discography.

Childhood

Curiously, despite being Hong Kong’s most famous jazz musician, Eugene’s first recollection of organised sound was that of classical music. “I used to wake up to sounds of the violin.” Eugene’s father, who was an amateur violinist, often practised the violin in the morning, playing along with classical records. Eugene was thus regularly listening to music when he was a child.

It was his American cousins, however, who kindled Eugene’s passion for music-making. Eugene still remembered their first visit to Hong Kong. “They brought along some 45-rpm single records, containing songs from the Beatles.” Eugene was immediately hooked by the catchy tunes, and, more importantly, their instrumental line-up. “The Beatles were a guitar-oriented band, and they inspired me to pick up the instrument.”

Eugene persuaded his father to buy him an acoustic guitar, and he started to teach himself how to play the instrument. His father also bought him a chordbook detailing the hand positions of each chord, and Eugene would follow the instructions and try to strum on the guitar. For a Primary Five student, it was not an easy endeavour. “I had to struggle just to make a sound. I remember not having enough strength to press the guitar strings – the tension on the strings was so strong that I could shoot arrows on them!”

Eugene also dabbled on the keyboard when he was in secondary school. “As part of the music curriculum, the school required us to play a classical piece on any instrument.” Eugene didn’t want to play a classical piece on the guitar, so his mother brought him to Tom Lee to look at the alternatives. “My mother saw a Yamaha electric organ there, and thought that it looked good, even as just furniture, so she brought it home.” The organ came with supplementary piano lessons, and this is how Eugene became proficient on the keyboard.

This early investment paid off later in Eugene’s life, when he joined a music production house specialising in movie and commercial soundtracks. Soundtrack production involves large amounts of programming on keyboard-like interfaces and controllers, and Eugene’s finger dexterity came in handy. “I am thankful that my mother pushed me to learn the keyboard back then.”

From Rock to Jazz

Despite his early acquaintance with music, Eugene’s guitar career did not start quickly. “By the time I graduated from secondary school, I had already no doubt I wanted to be a musician. I wanted to study music; I wanted to go to the Berklee College of Music.” Unfortunately, Eugene’s parents had other plans for their son. “Back then, there was a saying of 洋琴鬼, a derogatory term used to describe unruly foreign musicians in nightclubs. My parents thought that it was unbecoming to become a musician, and instead persuaded me to study business, in the hope that I could inherit the family business when I graduated.”

Eugene eventually gave in and obtained a degree in business. Even then, however, Eugene never stopped exploring music. “I listened to a lot of rock music in Hong Kong, but in my college life in Seattle my friends introduced me to fusion jazz.” The beginning of the eighties saw the rise of fusion jazz as a genre, and its combination of jazz and rock paved the way for Eugene to dive deep into the extensive history of jazz. “The familiarity of the rock element allowed me to understand the structures of fusion jazz, and this allowed me to appreciate the jazz side of the music even more.” Eugene was intrigued by the improvisations in the music, so he went to the library to research the topic. “Tracing the roots of fusion jazz’s improvisation, I came across big names such as Miles Davis and John Coltrane. When I got further up the list, I discovered masters like Charlie Parker or Dizzy Gillespie, and that eventually started my long journey with jazz.”

Of course, Eugene wasn’t content with merely listening to jazz. “My friends and I got together and listened to records all the time, and we also formed a band, learning songs from these albums and writing them out. We even tried out a few tunes and performed them in the college’s concerts.” Eugene even appeared on the 1984 album 香港 Xiang Gang, a compilation produced by the Hong Kong Guitar Journal. The owner of the journal, Lenny Kwok, invited five budding Hong Kong indie guitarists to collaborate on the album, and Eugene put forward two fusion jazz pieces, “Wear N’ Tear” and “Tapestry”. “I was still studying in Seattle that time, so I recorded my part there and sent the tracks by mail back to Hong Kong.” Incidentally, the album also featured contributions from Tats Lau before his venture into the Cantopop scene as Tat Ming Pair, as well as songs from Wong Ka Kui and Yip Sai Wing before they fully adopted the name of Beyond.

Chance Encounters

Eugene went back to Hong Kong shortly after his college graduation, working in his father’s company and running errands for him. However, Eugene eventually quitted the office job and heeded his true calling. “I was ready to start my professional playing career.” Working full-time in the regular house band of Rick’s Café in Tsim Sha Tsui, Eugene become close friends with Ric Halstead, a saxophonist and leader of the band. “Ric had an idea to do a record with me, and bassist Eddie Gomez was in town, coincidentally, concerting with the Steve Gadd Band. Ric called Eddie Gomez, Eddie said yes, and this was how I recorded my first full-length album, the aptly named Chance Encounters.”

Golden Ages

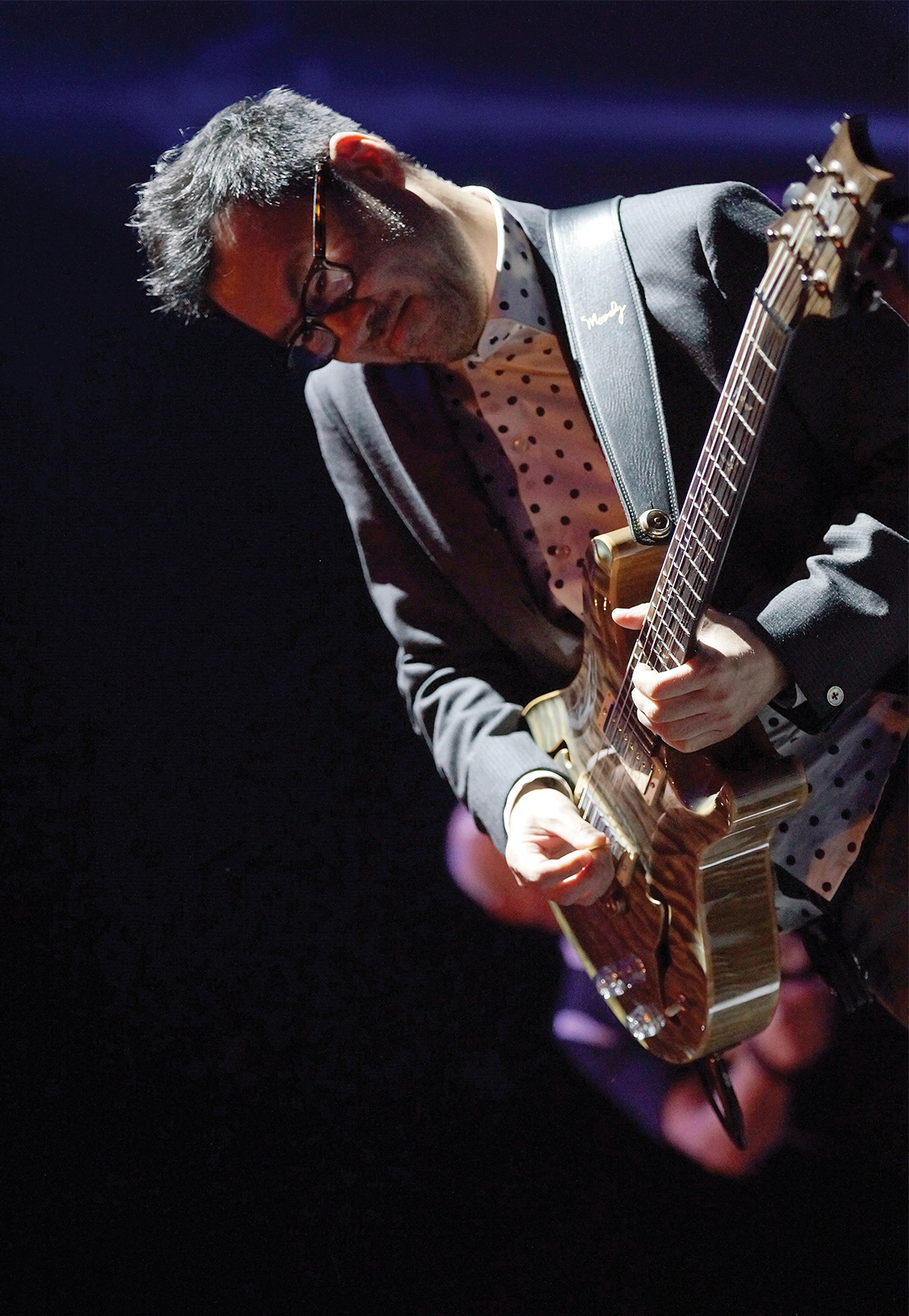

In 1989, Ric left Rick’s Café and became the music director in the Jazz Club and Bar in Lan Kwai Fong. Eugene followed through, and news soon spread of a happening guitar player in Hong Kong.

Photo credit: Jassman Wilson.

Eugene attributed much of his success to his years at the Jazz Club. “I was lucky to have started in the nineties. Nowadays musicians tend to travel with their own crew, but back in the nineties jazz clubs used to invite only the lead players from overseas to perform with their local, in-house bands. Famous players like Joe Henderson or Jon Hendricks would come and jam with us, and this provided a training ground for me, forcing me to learn on the spot, on and off, for more than ten years. It was that unique place, at that unique time, that allowed me to get off the ground.”

To Eugene, the Jazz Club (1989–2002) symbolised the golden age of the Hong Kong jazz scene. “The audience were mainly expats, and there were top international acts coming through.” The nineties saw a lot of concert tours by Western pop singers, who regularly employed jazz musicians in their bands. On their off-nights, those jazz musicians would swing by the jazz club, order one or two drinks, and enjoy the atmosphere. If they liked the music, they might even sit in and jam with the live band.

Eugene still remembered one such encounter with the legendary jazz pianist Herbie Hancock. “It was 1986, when Rick’s Café was still open. We caught wind of Herbie coming down to the café that night, so we prepared a keyboard in advance. He loved our playing so much, he sat in with us. Do you know what tune he called? ‘Maiden Voyage’.” “Maiden Voyage” was Herbie’s most famous composition, and Eugene was naturally nervous. Fortunately, all went well, and Herbie complimented Eugene after he’d finished playing. “Hey, man, you sounded great.”

Outlet

In a similar situation, Eugene also got to meet the great American saxophonist Michael Brecker. “In 1990, Warner (WEA) asked me for a one-time recording deal with my jazz fusion trio Outlet. As luck would have it, Michael Brecker was in town playing with Paul Simon (of Simon and Garfunkel fame) for a show in Hong Kong, so I reached out to him via Warner. He was one of my all-time favourite saxophone players.”

Michael agreed to play “In Search Of…”, one of Eugene’s own compositions. “I hadn’t written down any charts for the song, so I sat on the piano and played him some chords. My song didn’t have any melodies, so I even asked him if he could do his fills but make it more melodic, such that it could stand strongly as a melody as well.” Michael handled the requests with ease. “He took four takes, and each take was more amazing than the one before.” Eugene recalled having difficulty deciding which version to use. “It is Michael Brecker, after all. What else do you expect from a master?”

By the Company You Keep

Eugene played with Brecker again in 1994, this time in Brecker’s hometown. In a textbook case of youthful abandon, Eugene decided to record his debut album in New York. “My previous CDs were all collaborations with other artists, and I decided to make my own solo album.” Eugene had not signed a contract on the album at that time, so the entire trip was self-funded. “Looking back, it was quite brave of us to have done that.”

For bass and drums, Eugene called upon his connections. “During the time I was playing in the Jazz Club, I got to meet some of my jazz heroes who seemed to like my playing.” Eugene braced himself and proceeded to “cold-call” Jack DeJohnette and John Patitucci, expecting to get rejected. To his surprise, both accepted.

Eugene remembered how nerve-wracking it was in New York’s famous Clinton Studio, waiting for the three bigshots to walk in. Fortunately, the musicians were very welcoming and supportive, and the session completed successfully. Eugene was especially grateful to Jack DeJohnette, whom he described as almost “taking me under his wing”. “When listening to the playback, I can feel that they genuinely enjoyed everything. It was an unforgettable experience.”

After the recording, Eugene thought he had laid the proverbial golden egg. “With such a line-up, I surely would have no problem getting a contract from record labels.” Sadly, it turns out that signing a contract is a tricky business. “We met with labels like Blue Note Records, but they all rejected me, and told me that it was hard to promote me if I was not living in the States.” Some of the more helpful labels even advised Eugene to go back his own country and try to sign a local label there, but Eugene knew better. “Cantopop was the dominant music in Hong Kong in the nineties, and of course no Hong Kong labels were interested in such a far-out blowing record.”

Eugene eventually set his sights on Japan. “Japan had a vibrant jazz scene, and I thought I had better chances there.” Eugene ultimately entered into a licensing deal with Toshiba EMI, and in the process became the first Hong Kong-based jazz musician to have signed with an international record label.

Naked Time

By the Company You Keep was not Eugene’s only recording during his New York trip. “I recorded another album, Naked Time, within a week of By the Company You Keep.” As Eugene put it, By the Company You Keep is more of an acoustic blowing album, while Naked Time is more arranged, more fusion style. “I thought that, with two such contrasting styles, I would have a greater chance of getting picked up by a recording label.” As it turns out, while By the Company You Keep was released in 1996, it wasn’t until 2004 that Naked Time was picked up by EMI Music Hong Kong.

Eugene explained the differences between the two albums. “In terms of production, Naked Time is more produced – the rhythm section was first recorded, then other parts and some solos are overdubbed. Consequently, it took more time to record.”

This Window

After its release, By the Company You Keep sold several thousand copies, a considerable number by the standards of jazz records. Following the success, Sony Music Entertainment (Japan) approached Eugene. “The producer Kozo Watanabe, who would later become a good friend of mine, flew to Hong Kong to find me directly. He asked if I was interested to record another album in New York, this time with their full sponsor.”

The offer was a godsend for Eugene. “Sony gave us some cash advance, and we lived in Le Meridian, right next to Carnegie Hall. It was incredible.” The corporate sponsor also meant that Eugene could recruit all the big players, something made easier by Eugene’s excellent track record. “I contacted Jack DeJohnette for drums and Joey Calderazzo for piano, and they both accepted.” The choice for the bass player was less straightforward. “My first choice was Charlie Haden, but sadly he was in Los Angeles that time. For him to come, Sony would have needed to pay for two round-trip business class tickets: one for the musician and another for his bass.” Eugene finally chose Marc Johnson, who turned out to be a great player to work with. “Marc Johnson was a super nice guy; you can talk to him and tell him what you need, and he will have your back.”

This Window was released in 1999 in the all-new DSD recording format for Super Audio CDs (SACDs). “It was a clearer digital format, unlike conventional CDs. I was one of the first artists to be on this format.”

Pao

Fast forward a few years later, and by 2001 Eugene was ready for his next solo album, Pao. “By the Company You Keep, Naked Time and This Window were recorded with New York musicians, and so for the next record I wanted to work with European jazz musicians.” It turns out that Clarence, Eugene’s friend who helped fund By the Company You Keep, had a CD and record store and was the distributor of quite a few European labels. Through Clarence’s connections, Eugene got in contact with Stunt Records, who in turn hooked Eugene up with a recording deal in Copenhagen, playing with the Mads Vinding Trio.

Eugene had nothing but praise for Copenhagen. “I went to Copenhagen for a week or two, playing on the nylon string guitar and working with these wonderful European guys. The studio was amazing: it was so huge, and the recording quality was top-notch.” Eugene especially praised the upright bass. “They really nailed the acoustic bass sound.”

The Eugene Pao Project

Having played with American and European musicians, Eugene turned to Asia for his next major project. “There was a fad to film DVD concerts back in 2004. The businessman Wu Chung (whom the Wu Chung House was named after) was into video-recording, so his company asked if I was interested in a multimedia project where multiple cameras would be used to film our playing.” Eugene accepted, and thus The Eugene Pao Project was born.

To allow the cameras to capture multiple angles, Eugene proposed to host a live concert without an audience. “That way, we do not bore anyone when we repeat the pieces!” The venue was set in HKAPA’s concert hall, and Eugene remembered all the extravagant cameras and lighting. “It was a huge production.”

Eugene hand-picked the band for this recording. “I picked musicians from all around Asia.” The cast was quite diverse, comprising Malaysian percussionist Steve Thornton, Filipino saxophonist Tots Tolentino, Japanese drummer Tamaya Honda and bassist Shigeo Aramaki, as well as the Hong Kong-based keyboardist Ted Lo and vocalist Angelita Li.

The album also featured another technical innovation, 5.1 surround sound. “As the producer of the project, this was my first time mixing in 5.1 surround sound. It was a cool experience to mix and to decide the placement of speakers.”

Asian Super Guitar Project

The Eugene Pao Project left Eugene wanting for more, and within the year he had already conceived of another project. “I had the idea to do a guitar trio, featuring musicians of Chinese, Korean and Japanese ethnicity – three races that had always had tense relationships with each other.” The idea, as Eugene explained, was to show that, despite their differences in nationality, players could still get together and make good music. The trio consisted of the Korean guitarist Jack Lee, Japanese guitarist Kazumi Watanabe, and Eugene as the Chinese representative.

Eugene and Kazumi’s relationship went way back. “Kazumi was one of my idols since I was young. In 1986, I had the chance to meet Kazumi and performed together with him at the Live Under the Sky festival, one of the big three jazz festivals in Japan. That year was the first time the festival was imported to Hong Kong, so the idea was to find a Hong Kong local artist to crossover with a Japanese artist. They chose me and Kazumi, so I flew over to Japan for a performance with him, and then he came over to Hong Kong for another concert in Queen Elizabeth Stadium. That was how I met Kazumi.”

Recording for the Asian Super Guitar Project took place in Seoul in 2006, and the project culminated in a regional tour around Asia. “We went to the Hong Kong City Hall for a show, and performed in concerts in Japan, Korea, Malaysia and Singapore.”

To Paris with Love

Eugene teamed up with Jeremy Monteiro for an album in 2015. “Jeremy Monteiro is a really big deal. He is Singapore’s most representative jazz musician, and he was awarded the government’s cultural award for his contribution to the arts and jazz music of Singapore.”

Eugene and Jeremy had collaborated with each other before, but this was the first time they had worked as a duo. “Jeremy had the idea to make an album as a tribute to the music of Michel Legrand.” Michel Legrand, a French composer, was most famous for his movie soundtracks, but he was also known in the jazz scene as a prolific writer of jazz tunes. Many of Legrand’s compositions, like What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life, had since became jazz standards.

At Jeremy’s insistence, the two went to Germany to record the album. “Jeremy said that there was a place in Germany that had the best grand piano for recording, so we went to this studio in Darmstadt. It’s just Jeremy on piano and me on guitar, and we finished the recording within a few days.”

(From right to left) Eugene Pao, Brian Hurley and Alex Ho at Peel Freco (2019) (Photo credit: James Ho).

Evolution

Since his first gig in Rick’s Café, Eugene had played jazz for more than thirty years. Naturally, his jazz style had evolved over the years as well.

“When I started playing, jazz fusion was the fad, and I was really influenced by the big threes of jazz fusion, Chick Corea’s Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, and Weather Report. Afterwards, I discovered Pat Methany, John Scofield, Mike Stern, along with other modern jazz players. Through them, I discovered the whole jazz history, where they came from, and eventually I learnt more about bebop.”

The language of bebop did not come naturally to Eugene. “After I listened to a lot of jazz records, I could feel the bebop language. But to play it, especially on the guitar, is a fiendishly challenging journey.” Eugene notes the difficulties of the instrument. “It is easy to jump across large intervals on the piano; you simply have to stretch your hands. It is a totally different concept on the guitar, where you have to switch between the strings as well.”

The fretboard-pressing nature of guitar is also not conducive to bebop’s coherent playing style. “Smoothness is not a problem on saxophones; it’s as natural as breathing in and out. On the guitar, however, there is less sustain between the notes, so it’s easy to sound too staccato, too much like a typewriter. You need to put in more effort to evoke the audience’s emotions.”

As Eugene’s style matured, he increasingly felt the need to connect with the audience. “I always asked myself, how many percent of my typical audience are musicians? Not a lot, right? That’s why, instead of relying on virtuosity, you have to touch them musically.

“Let’s say you invented a new spicy pattern, this diminished lick over a certain chord. You might marvel at your own ingenuity, but, if it’s not musical, then you can’t move the audience; it is just a bunch of notes, it’s meaningless.

“Music is not about how fast you can play. It’s about finding those sweet notes and bringing them together in a melodic way, so that you can move the audience. This involves a lot of things: your sound, your instrument, your touch, tone, choice of notes, and of course the knowledge of music theory. It is indeed an advanced skill to be able to just play a few notes and make the audience feel something, and I will probably spend the rest of my life trying to achieve this.”

Interviewed by Vantage Music, written by Chester Leung